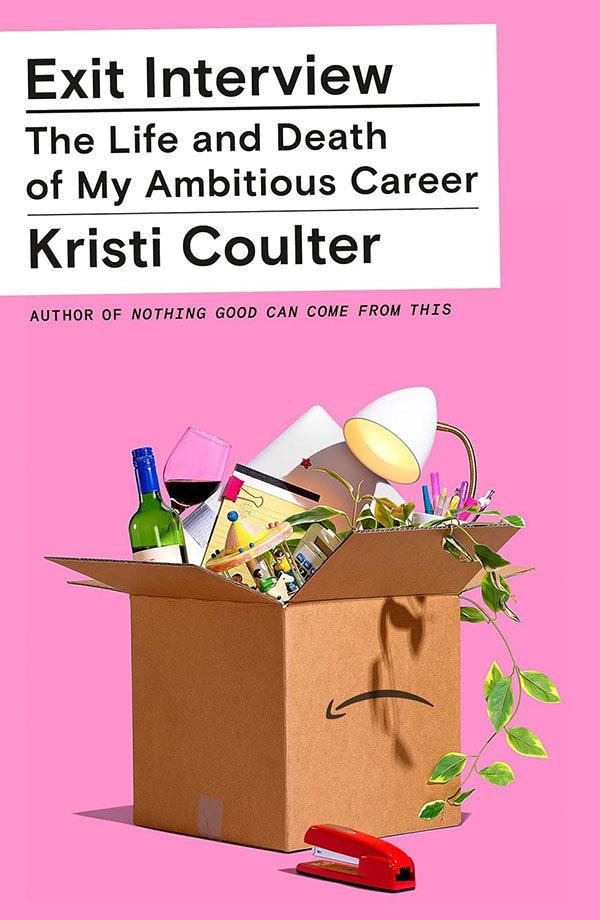

Exit Interview: The Life and Death of My Ambitious Career

by Kristi Coulter

During a recent quit-lit kick, I came across Kristi Coulter’s book of essays Nothing Good Can Come from This about her decision to quit drinking. I soon discovered she was at work on a new memoir, this time about the twelve years she worked at Amazon.

In 2019, Electric Lit magazine published “Where Are All the Memoirs About Women and Work?” and earlier this year Forbes posted a “must read” list of books about women in the workplace that didn’t include a single memoir.

Mary Louise Kelly recently wrote It. Goes. So. Fast. about raising two sons while working as a successful journalist and anchor of NPR’s All Things Considered, but Kelly had spent her career in war zones, interviewing world leaders and being a general badass, while I’d spent my days in windowless conference rooms drenched in sweat for no particular reason.

Kelly details an exchange with former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, after which he falsely accused her of lying. He also implied she was unable to identify Ukraine on a map and had instead pointed to Bangladesh (she had not). While I (too) know that Ukraine is not in South Asia, I am no Mary Louise Kelly.

With my own memoir about work languishing in a desk drawer, I’d been waiting for a book like Coulter’s. Unlike Kelly, Coulter and I had similar raw material — a mid-level job in corporate America. Her new book Exit Interview: The Life and Death of My Ambitious Career details what it was like to be well-paid while working for the quintessential soul-sucking corporate employer that is Amazon.

I had questions. Would details about the day-in and day-out of her job be boring? Could a story that takes place almost exclusively in an office be interesting? These fears and more have kept my own memoir tucked safely away in that drawer.

Coulter opens the book with a description of Amazon in the mid-aughts. Meetings so stressful that participants popped beta-blockers beforehand. Duct-taped laptops. Therapists’ luxury vacations funded solely by sessions with Amazon employees. Firing by algorithm.

Still, Coulter was drawn to the excitement of it all:

For twelve years Amazon supplied me with a high-grade lunacy I didn’t know I needed until I touched it and my ambition bloomed like neon ink in water. That doesn’t sound fun, the faces say. Or that shouldn’t have been fun. To which my only possible response is, I’m not telling you what was right or good. I’m telling you what went down and how it felt.

She opens the book with a humorous job posting similar to the one she would eventually accept. She describes the seven-hour interview she endured to land that job. She writes about a leadership development program in such detail that it felt like I was in the two-day meeting with her.

While Coulter is an expert storyteller—I was always eager to read what came next—she never quite got to what my writing teacher calls “under the under.” Coulter tells me what happened, but she leaves out much of what it meant to her. What had this job done to her self-worth? Why did she stay for so long? How does a bright, ambitious woman who delivers value to an organization as profitable as Amazon not get promoted? Is Amazon unique or universal?

Her journey ended with something akin to it was sometimes fun while it lasted. My main takeaway wasn’t revelatory, it was simply this: Never work for Amazon.